I’ve just returned home after three weeks of trainings in Zambia, South Africa and Mauritius. Last week our team of trainers journeyed from Ndola to Cape Town to begin our People’s Seminary four-day module “Christian Identity and Mission in Scripture and Society” in the battle-worn township of Manenberg. There we saw how essential it is to bring together careful study of the Bible with the gifts of the Spirit together with street and Scripture-informed justice.

We were hosted by Tree of Life, a ministry to gang-involved youth that includes a vibrant faith community that’s been active in the township since 2013. We stayed in one of the gang-neutral Muslim neighborhoods where Tree of Life is based. According to Tree of Life’s website:

“Manenberg was established between 1966 and 1970, under the South African apartheid regime’s forced removals of ‘non-whites’ from the various suburbs of Cape Town that had been deemed ‘whites only’. Many families were ousted from their homes at the foot of Table Mountain, split up, and thrown into substandard housing with little formal infrastructure, 20km out of town. Midst the trauma of family dislocation, fear, and loss of safe space, gangs formed. Brotherhoods of disillusioned young men rapidly spread throughout Manenberg and the Cape Flats. The rotten legacy of Cape Town’s apartheid past has given rise to violence, crime and drug abuse in pandemic levels.

Today, Manenberg suffers daily, and the effects are seen throughout the whole family, fractured relationships, high levels of domestic abuse and a home environment that does not provide a safe place for young children to grow up.”

As our host Pete Portal drove us into the community it felt like we were entering a sort of run-down war zone. Churches and mosques were everywhere, often surrounded by high fences with razor-wire. The first thing we were told was to not walk around the township without being escorted by one of their local staff.

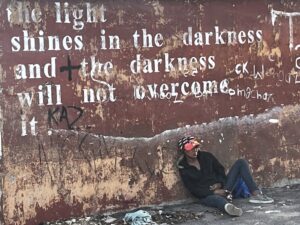

One of the first sights I noticed that embodied the contradictions is the photo above of a woman struggling with addiction leaning against a wall with John 1:5 written on it.

One of the first sights I noticed that embodied the contradictions is the photo above of a woman struggling with addiction leaning against a wall with John 1:5 written on it.

The next morning we started our Certificate in Transformational Ministry at the Margins with 35 or so people. The group was diverse, including staff, ministry workers from other organizations and a number of men and women in their twenties, who’d left their lives of drugs and gangs to live recovery-oriented community houses.

We began with worship and then launched into our first Bible studies on Genesis 1-4 and 12. To make the teaching more accessible to less-educated participants we used bibliodramas throughout.

Richard, our Zimbabwean pastor colleague played God in our session on Genesis 4. Rene, a tall, muscular German guy who does prison ministry played Cain. I gave him two apples to set them on a table in front of God (Richard). A young man who grew up on the streets of Manenberg played Abel. He brought a stuffed white lamb and laid it before Richard. Richard (God) looked upon Abel and his offering, and not upon Cain and his offering. Witnessing firsthand a contemporary manifestation of God’s unexplained preference for the underdog got everyone’s attention.

When Cain became angry, God approached him tenderly, and Richard asked him: “Why are you angry Cain?” This and God’s ongoing conversation with Cain showed everyone clearly how sin does not separate God from offenders. Rather we must expect God to show up and engage us when we’re angry or even committing acts of violence. “Do we expect God to draw close to us when we’re angry? Why are we angry?” we ask.

Acting out this text was especially powerful in a post-apartheid setting, where it’s still a shock to see God as a Black man and Cain as someone who looks like a privileged White South African. God’s looking upon the lower-status Abel surprised people, and his victimization led to a longer discussion on Jesus (and God’s) identification with Abel. Participants made these discoveries together in regular breakout groups.

Later that afternoon one of Tree of Life’s local leaders, Rudy, gave us a walking tour through the township. As we walked we were struck by a feeling of despair, visible in garbage strewn fields that were often the sites of battles between gangs with names like the Americans, Hard Living, Clever Kids, Fancy Boys, Jester Kids, Dixie Boys, Junky Funky. We could see the relevance of contextual Bible studies like the one we’d just done for this community torn by violence.

The next day we presented on Isaiah 1-39, looking at how the prophet articulated God’s opposition to the status quo of oppression, one of our particularly street/justice-oriented studies. A Black South African woman named Blondie, who’d done twelve years in prison and now works for a ministry to ex-offenders played the prophet Isaiah.

The next day we presented on Isaiah 1-39, looking at how the prophet articulated God’s opposition to the status quo of oppression, one of our particularly street/justice-oriented studies. A Black South African woman named Blondie, who’d done twelve years in prison and now works for a ministry to ex-offenders played the prophet Isaiah.

We looked at distinctions between the powerful and weak in Isaiah 1-5, and had people talk about the distinctions in Cape Town. The people identified some of the big corporate grocery story chains as embodying the powerful, and minimum-wage employees being today’s equivalents of the poor in Isaiah.

I’d asked a White Church of England clergyman whether he’d be willing to play the CEO of Woolworths, one of the powerful corporations identified by the group. He agreed and I began by interviewing him, asking him how much his yearly salary was. He told the group in an entitled way, and I asked the group what minimum-wage workers earners in a year. I then asked Blondie to stand up and speak out Isaiah 3:14-15 to the White Woolworths CEO.

At first she read the Isaiah 3 haltingly and softly, and I encouraged her to belt it out like she was Isaiah the prophet. She then boldly read:

“The Lord enters into judgment with the elders and princes of his people, “It is you who have devoured the vineyard; The plunder of the poor is in your houses. “What do you mean by crushing my people and grinding the face of the poor?” Declares the Lord God of hosts.”

Watching and listening to Blondie speak out these words to a White man was one of the most powerful moments of the training. The S. African course participants seemed especially gripped by this, and God’s clear siding with the poor against oppressors seemed to sink in deeply.

This was followed by my Swedish colleague Andreas’ powerful treatment of the prophet Isaiah’s own call in the temple in Isaiah 6. There when encountered by the Lord he saw himself as unclean, in no way superior to any he might otherwise discriminate against. This was followed by our South African colleague Colleen’s treatment of the Servant of the Lord in Isaiah 40-55, where we see how God recruited oppressed exiles for his missional movement to the world.

After that I did a teaching on Jesus’ baptism, where we saw how Jesus himself identifies with God’s enemies by symbolically dying there in the Jordan River, which was followed by his departure from his homeland—a necessity for anyone seeking to follow Jesus as a disciple.

In our next study Richard then played Jesus, and Andreaz the devil, and Richard modeled how to confront the tempter, making Jesus’ wilderness temptations come alive for people.

Colleen led the group in a spiritual mapping exercise, and people presented the Manenberg township and we prayed together.Another highlight was when we modeled how to pray for healing, and the first person we prayed for was healed before the group. Andreaz then invited someone who had never prayed for healing to come and pray for one of the course participants, who was suffering from back pain. One of the former gang-member street youth volunteered to pray, and I found myself worrying whether we were setting things up for an awkward failure.

I invited the young man to ask permission from a woman to place his hand on her back to pray for her. He dutifully asked her and she gave him permission. I then invited him to order the pain to leave her back in Jesus’ name, based on Jesus’ imperatives when he healed people. He ordered the pain to go and we asked Fatima if she noticed any change. “No,” she said. “It’s still the same.”

I then invited the young man just to pray again however he felt led to pray, using his own inspired words. He prayed a beautiful prayer and the woman suddenly declared with surprise and delight that all the pain was gone (see photo below). Within an hour of completing the training we learned that three people were killed in gang-related violence in the township. We ourselves saw the body of man covered with a white sheet at the crime scene, and learned he’d killed someone before being hunted down himself and beaten to death in front of some of Tree of Life’s local leaders’ house.

Within an hour of completing the training we learned that three people were killed in gang-related violence in the township. We ourselves saw the body of man covered with a white sheet at the crime scene, and learned he’d killed someone before being hunted down himself and beaten to death in front of some of Tree of Life’s local leaders’ house.

That night we gathered for Tree of Life’s monthly Kingdom Come worship service, where we lamented these deaths, interceded for the community and ended with a healing service. Many people came up for prayer, and the Spirit of God moved powerfully to bring relief. In places like Manenberg the urgency of proclaiming a liberating Gospel and seeing God’s Kingdom come is certainly apparent. May we continue to pray that God’s Kingdom will come, God’s will be done, on earth as in heaven, and open ourselves to being part of Jesus’ liberation movement.

That night we gathered for Tree of Life’s monthly Kingdom Come worship service, where we lamented these deaths, interceded for the community and ended with a healing service. Many people came up for prayer, and the Spirit of God moved powerfully to bring relief. In places like Manenberg the urgency of proclaiming a liberating Gospel and seeing God’s Kingdom come is certainly apparent. May we continue to pray that God’s Kingdom will come, God’s will be done, on earth as in heaven, and open ourselves to being part of Jesus’ liberation movement.

Take a look at our self-paced online Certificate in Transformational Ministry at the Margins here.

Check out my interview with Pete Portal on my Disciple podcast below, and last week’s interview with Richard Malitino.